September 30, 2011

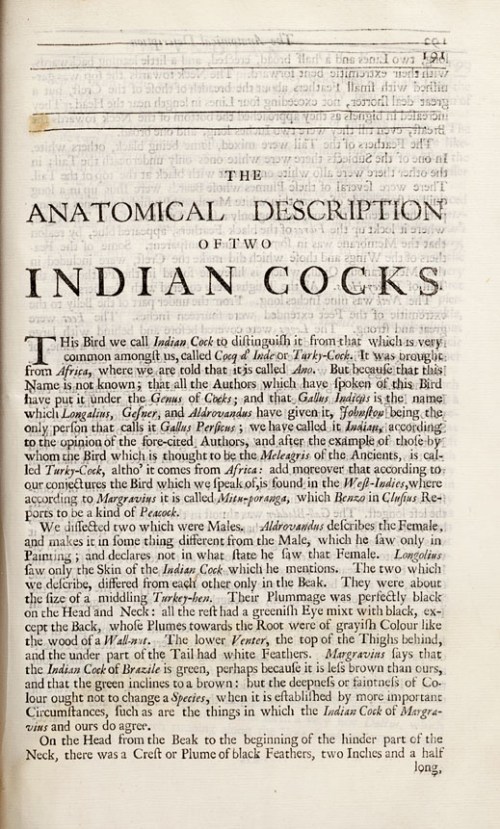

Anatomical description of two Indian Cocks. Example of scientific literature that isn’t quite what you expect.

From Memoir’s for a natural history of animals : containing the anatomical descriptions of several creatures dissected by the Royal Academy of Sciences at Paris

By Claude Perrault, 1688.; hat tip to Fresh Photons.

September 30, 2011

Sciencegeek Fundamentals #1: An Introduction to the Scientific Method, by way of Chewbacca

A TANGENTIAL SCIENTIFIC METHOD:

ON THE NATURE OF SCIENCE WITH REFERENCES TO CHEWBACCA, STORK EATING ALIENS, A FEW STEVES, ONE INSTANCE OF THE WORD “FUCK,” AND (QUITE POSSIBLY) TWO VERY LARGE CHILDREN.

By DAVID NG

(Fancy pdf of this piece in its entirety also available here)

For the last couple of years, when I’m speaking or lecturing to a larger audience, I would sometimes throw out the following question: “Who is Chewbacca?”

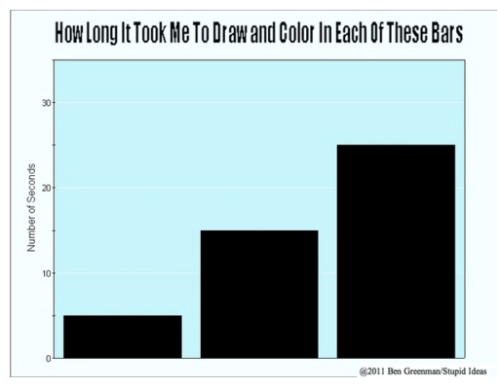

I do this because I’m curious on whether there are actually people in this world who have never heard of Chewbacca. Which, as a big fan of Star Wars, is a possibility that escapes me. Still, without fail, there are always a few. In fact, if I were to plot graphs around this question, I would notice that “Ignorance of Chewbacca” has been going up in a slow but steady fashion over the last few years. Furthermore, my small and caveat laden sample of data currently suggests that at least 5% of the world has no clue what this Chewbacca thing is [1].

Then, of course, things would get strange. Because usually at this point, I might ask those knowledgeable in the audience, to describe “Chewbacca” to those who are not. Here, the references to Star Wars specifically and science fiction in general come out. This includes discussions about co-piloting space ships, ripping arms off, and descriptions of a weapon that is a cross between a laser and a crossbow. The word “wookie” will inevitably surface, and then, remarkably you might say, someone will begin to make Chewbacca sounds – something best described as a long vibrating groan suggestive of yearning [2]. Indeed, if I give it a chance, the whole lecture hall might even begin making Chewbacca sounds, which is something that is both uniformly glorious and bizarre at the same time. Interestingly, none of this really seems to help the 5% who confessed to being Chewbacca ignorant. If anything, the 5%, looking at the strange proceedings around them, tend to look confused if not a little frightened.

I bring this up, because this silly idea of Chewbacca ignorance is a bit like asking people, “What is science?” It’s one of those things where a proper answer is actually very rich in detail, and nuanced in ways that can be surprising. Furthermore, these details and nuances tend to be only obvious to those firmly embedded within science culture itself. And much like the Chewbacca example, if you explain this to a person who is not part of this culture, it would probably sound a little bewildering and frightening too.

To illustrate this, let’s try something right now. Find someone you know who isn’t into science.

This is probably pretty easy, since this is likely most people. Now ask them point blank, “What is science?” Undoubtedly, you will get all manner of responses – many of which will reference graphs, measurements and technology, perhaps with nods to things like physics, chemistry and biology. But if you listen carefully, I would bet that the responses are vague at best, and certainly not a reflection of the richness involved in what I consider a proper answer. Sort of like the injustice that goes with describing Chewbacca as simply, “a character in a science fiction movie.”

To me, this is a shame. Not the Chewbacca part (which is a different kind of shame), but the bit about science. To me, the idea of the general public reacting to the fundamentals of science literacy, in a way that the aforementioned 5% might react to a wookie sound, is a very bad thing. In fact, I would suggest that this confusion or lack of familiarity over science is actually a dangerous thing. This is because, unlike wookies, science has an increasingly active and prominent role in real life.

As well, this lack of clarity is not about science literacy in the sense that we worry about citizens who do not know about greenhouse gases, or how DNA is replicated, or how differential calculus is done – in other words, it’s not really about specific technical details (although this is important too). But rather, it is mostly about whether a person is literate of the process; whether they appreciate the steps and parameters which define how science is done. It is mostly about these points because they represent a framework that provides the world with a very powerful way of knowing things (epistemology for those who prefer big words).

Such parameters, of course, are often neatly laid out in what many would call “The Scientific Method.” Almost everyone will hear about this at some point in their lives, although it appears to be a topic that mostly presents itself at younger ages, at the elementary school levels for instance. However, one also finds that as the student gets older, its premise will be continually diluted by an increasing glut of science technical detail. This is an unfortunate reality of how science is taught in schools – there are information hierarchies that must be covered in order to get to the next level, and because the volume of that information is intense, there is simply little time for students to reexamine the basic principles of the scientific method and of science culture itself. Furthermore, this does not even include those young students who decide to avoid the sciences altogether.

Which brings us back to aforementioned mention of shame. After all, shouldn’t we encourage all students and citizens to continually reassess the scientific method: more so, since an elementary student is hardly in the best position to fully appreciate its complexity? Isn’t the scientific method an icon of rationality – something that you hope all decision makers, from individuals making small choices to leaders making large ones, would take time to appreciate fully?

Unfortunately, this isn’t how the world currently works. Which is disappointing: because regardless of all this talk about society and danger and decisions, it would do us well to be reminded that through it all, the Scientific Method (and what it has produced) is, quite frankly, awesome.

So for now, we’ll end this section with something basic. We’ll end it with a flowchart depicting the scientific method. Perhaps something with steps like the below:

1. See something.

2. Think of a reason why.

3. Figure out a way to check your reason.

4. And?

5. Now, everyone gets to dump on you.

6. Repeat, until a consensus is formed.

But don’t forget: this representation is, by no means, a complete picture or even necessarily a correct picture. Indeed, Sir Francis Bacon himself, a man often considered to be the “Father of Scientific Method,” [3] may disapprove with the simplicity of this flowchart.

It is, however, as good a place to start as any: and hopefully sufficient to at least utter the sentiment, “Punch it Chewie.”

Notes

[1] If you happen to be part of this 5%, please refer to this link for more on Chewbacca.

[2] The Chewbacca Soundboard.

[3] Sir Francis Bacon (1561 – 1626) was incredibly influential in highlighting the importance of “inductive reasoning” through the accumulation of data (also sometimes called the Baconian Method). he was also buddies with the British Monarchy, and there exists many a hypotheses that suggests he may have written some of the works of Shakespeare.

(3rd draft)

Featured

A place of mostly science, art, writing and occasionally Chewbacca, all lovingly archived by Dave Ng. For recent highlights just scroll down, but also note the handy tag system (for finding that piece of media for your next science talk) just below. Enjoy!

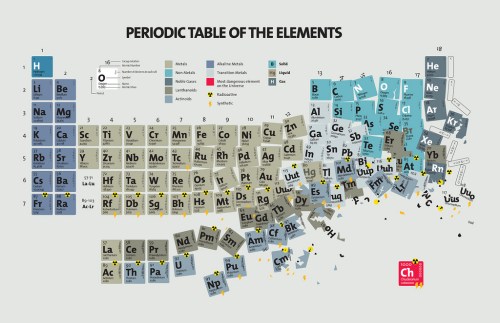

FIND ME SOMETHING AWESOME ABOUT

anatomy, astronomy, biochemistry, biodiversity, biology, botany, cell biology, chemistry, chewbacca, climate change, data, dinosaurs, energy, entomology, environment, evolution, food, fossil fuels, genetics, geography, geology, graphs, laboratory, marine life, math, medicine, microbiology, molecular biology, neuroscience, ornithology, paleontology, physics, planetary science, quantum physics, science careers, science history, science literacy, scientific method, scientist, solar system, space, strange paper, sustainability, technology, zoology

September 29, 2011

The importance of stupidity.

“I recently saw an old friend for the first time in many years. We had been Ph.D. students at the same time, both studying science, although in different areas. She later dropped out of graduate school, went to Harvard Law School and is now a senior lawyer for a major environmental organization. At some point, the conversation turned to why she had left graduate school. To my utter astonishment, she said it was because it made her feel stupid. After a couple of years of feeling stupid every day, she was ready to do something else.

I had thought of her as one of the brightest people I knew and her subsequent career supports that view. What she said bothered me. I kept thinking about it; sometime the next day, it hit me. Science makes me feel stupid too. It’s just that I’ve gotten used to it. So used to it, in fact, that I actively seek out new opportunities to feel stupid. I wouldn’t know what to do without that feeling. I even think it’s supposed to be this way. Let me explain. (read more).

A great article by Martin Schwartz on what makes research both scary and downright wonderful.

September 29, 2011

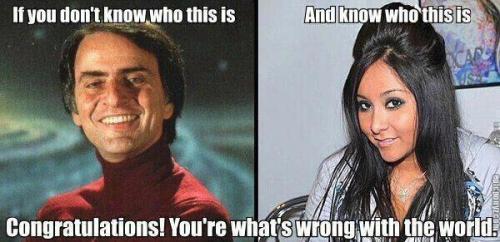

How to know if you are what is wrong with this world.

For the record, I’m inclined to agree.

September 26, 2011

As discussed by Collins and Dawkins – God versus Science. Who wins? #SCIE113

An interesting link sent to me from @joannealisonfox. Read the preamble below, and then click to go to the link where the actual conversation between Collins and Dawkins is transcribed.

Question to ponder as you do this… Who wins the discussion?

There are two great debates under the broad heading of Science vs. God. The more familiar over the past few years is the narrower of the two: Can Darwinian evolution withstand the criticisms of Christians who believe that it contradicts the creation account in the Book of Genesis? In recent years, creationism took on new currency as the spiritual progenitor of “intelligent design” (I.D.), a scientifically worded attempt to show that blanks in the evolutionary narrative are more meaningful than its very convincing totality. I.D. lost some of its journalistic heat last December when a federal judge dismissed it as pseudoscience unsuitable for teaching in Pennsylvania schools.

But in fact creationism and I.D. are intimately related to a larger unresolved question, in which the aggressor’s role is reversed: Can religion stand up to the progress of science? This debate long predates Darwin, but the antireligion position is being promoted with increasing insistence by scientists angered by intelligent design and excited, perhaps intoxicated, by their disciplines’ increasing ability to map, quantify and change the nature of human experience. Brain imaging illustrates–in color!–the physical seat of the will and the passions, challenging the religious concept of a soul independent of glands and gristle. Brain chemists track imbalances that could account for the ecstatic states of visionary saints or, some suggest, of Jesus. Like Freudianism before it, the field of evolutionary psychology generates theories of altruism and even of religion that do not include God. Something called the multiverse hypothesis in cosmology speculates that ours may be but one in a cascade of universes, suddenly bettering the odds that life could have cropped up here accidentally, without divine intervention. (If the probabilities were 1 in a billion, and you’ve got 300 billion universes, why not?)

Roman Catholicism’s Christoph Cardinal Schönborn has dubbed the most fervent of faith-challenging scientists followers of “scientism” or “evolutionism,” since they hope science, beyond being a measure, can replace religion as a worldview and a touchstone. It is not an epithet that fits everyone wielding a test tube. But a growing proportion of the profession is experiencing what one major researcher calls “unprecedented outrage” at perceived insults to research and rationality, ranging from the alleged influence of the Christian right on Bush Administration science policy to the fanatic faith of the 9/11 terrorists to intelligent design’s ongoing claims. Some are radicalized enough to publicly pick an ancient scab: the idea that science and religion, far from being complementary responses to the unknown, are at utter odds–or, as Yale psychologist Paul Bloom has written bluntly, “Religion and science will always clash.” The market seems flooded with books by scientists describing a caged death match between science and God–with science winning, or at least chipping away at faith’s underlying verities.

Finding a spokesman for this side of the question was not hard, since Richard Dawkins, perhaps its foremost polemicist, has just come out with The God Delusion (Houghton Mifflin), the rare volume whose position is so clear it forgoes a subtitle. The five-week New York Times best seller (now at Number 8 ) attacks faith philosophically and historically as well as scientifically, but leans heavily on Darwinian theory, which was Dawkins’ expertise as a young scientist and more recently as an explicator of evolutionary psychology so lucid that he occupies the Charles Simonyi professorship for the public understanding of science at Oxford University.

Dawkins is riding the crest of an atheist literary wave. In 2004, The End of Faith, a multipronged indictment by neuroscience grad student Sam Harris, was published (over 400,000 copies in print). Harris has written a 96-page follow-up, Letter to a Christian Nation, which is now No. 14 on the Times list. Last February, Tufts University philosopher Daniel Dennett produced Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon, which has sold fewer copies but has helped usher the discussion into the public arena.

If Dennett and Harris are almost-scientists (Dennett runs a multidisciplinary scientific-philosophic program), the authors of half a dozen aggressively secular volumes are card carriers: In Moral Minds, Harvard biologist Marc Hauser explores the–nondivine–origins of our sense of right and wrong (September); in Six Impossible Things Before Breakfast (due in January) by self-described “atheist-reductionist-materialist” biologist Lewis Wolpert, religion is one of those impossible things; Victor Stenger, a physicist-astronomer, has a book coming out titled God: The Failed Hypothesis. Meanwhile, Ann Druyan, widow of archskeptical astrophysicist Carl Sagan, has edited Sagan’s unpublished lectures on God and his absence into a book, The Varieties of Scientific Experience, out this month.

Dawkins and his army have a swarm of articulate theological opponents, of course. But the most ardent of these don’t really care very much about science, and an argument in which one party stands immovable on Scripture and the other immobile on the periodic table doesn’t get anyone very far. Most Americans occupy the middle ground: we want it all. We want to cheer on science’s strides and still humble ourselves on the Sabbath. We want access to both MRIs and miracles. We want debates about issues like stem cells without conceding that the positions are so intrinsically inimical as to make discussion fruitless. And to balance formidable standard bearers like Dawkins, we seek those who possess religious conviction but also scientific achievements to credibly argue the widespread hope that science and God are in harmony–that, indeed, science is of God.

Informed conciliators have recently become more vocal. Stanford University biologist Joan Roughgarden has just come out with Evolution and Christian Faith, which provides what she calls a “strong Christian defense” of evolutionary biology, illustrating the discipline’s major concepts with biblical passages. Entomologist Edward O. Wilson, a famous skeptic of standard faith, has written The Creation: An Appeal to Save Life on Earth, urging believers and non-believers to unite over conservation. But foremost of those arguing for common ground is Francis Collins.

Collins’ devotion to genetics is, if possible, greater than Dawkins’. Director of the National Human Genome Research Institute since 1993, he headed a multinational 2,400-scientist team that co-mapped the 3 billion biochemical letters of our genetic blueprint, a milestone that then President Bill Clinton honored in a 2000 White House ceremony, comparing the genome chart to Meriwether Lewis’ map of his fateful continental exploration. Collins continues to lead his institute in studying the genome and mining it for medical breakthroughs.

He is also a forthright Christian who converted from atheism at age 27 and now finds time to advise young evangelical scientists on how to declare their faith in science’s largely agnostic upper reaches. His summer best seller, The Language of God: A Scientist Presents Evidence for Belief (Free Press), laid out some of the arguments he brought to bear in the 90-minute debate TIME arranged between Dawkins and Collins in our offices at the Time & Life Building in New York City on Sept. 30. Some excerpts from their spirited exchange:

September 26, 2011

The N.I.H. rejects Dr. Phil

By DAVID NG

Dear Dr. Phil,

Thank you for submitting your application for the director’s position at the National Institutes of Health. As the N.I.H. is the principal force guiding America’s efforts in medical research, we have strived to consider every candidate’s application seriously.

Our first impression was not a good one. You have a loud and exuberant manner that is an oddity in our network of colleagues, and for the duration of the interview process, you were physically sitting on top of Dr. James Watson (a man considerably smaller than you), oblivious to his muffled and strained murmurs beneath you. We found this quite distracting and wonder what this reflects of your character. Furthermore, although he has only a minor role in the selection process, the Nobel laureate was quite put out. As the conversation continued, we found other characteristics that troubled us. Your commitment to, as you call it, “big ideas,” whilst commendable, seemed a tad impetuous. Your mention of using your television program or perhaps “your good friend” Oprah’s television program to (in your own words) “GIVE FREE GENE THERAPY TO EACH AND EVERY MEMBER OF THE AUDIENCE!” is frankly very unsettling to us.

In truth, we fear that your celebrity status may ultimately impede our principal mandate of excellence in health research. Although some of our members thought it wonderful that you have a Muppet in your likeness on “Sesame Street,” your list of other references (e.g., “I drink scotch with Kelsey Grammer on a regular basis”) hardly elicits confidence. To be blunt, your scientific C.V. is poor and your repeated attempts to demonstrate your scientific prowess were laughable at best. (Adjusting the pH in your hot tub does not count, nor does your vasectomy.)

Finally, we found your tendency to talk in meaningless, corny phrases very irritating. Responses like “Sometimes you just got to give yourself what you wish someone else would give you” or “You’re only lonely if you’re not there for you” are very confusing, to say the least. In fact, our members felt that overall you were even more irritating than the applicant who used the word “testicular” 67 times in his interview. One member of our hiring committee actually wrote the comment “Who the [expletive] is this guy—Foghorn Leghorn doing Yoda?”

Consequently, the hiring committee regrets to inform you that your application has not been shortlisted for further consideration at this time. Please tell Ms. Winfrey to stop bothering us.

Yours sincerely,

Dr. Paul Batley Johnson

Hiring Committee

National Institutes of Health

(One of my older humour pieces – original link here)

September 23, 2011

Microbiological laboratory hazard of bearded men.

Barbeito, MS; Mathews, CT; Taylor, LA (1967). “Microbiological laboratory hazard of bearded men”. Applied microbiology 15 (4): 899–906. PMID 4963447

“An investigation was conducted to evaluate the hypothesis that a bearded man subjects his family and friends to risk of infection if his beard is contaminated by infectious microorganisms while he is working in a microbiological laboratory. Bearded and unbearded men were tested with Serratia marcescens and Bacillus subtilis var. niger.Contact aerosol transmission from a contaminated beard on a mannequin to a suitable host was evaluated with both Newcastle disease virus and Clostridium botulinum toxin, type A. The experiments showed that beards retained microorganisms and toxin despite washing with soap and water. Although washing reduced the amount of virus or toxin,a sufficient amount remained to produce disease upon contact with a suitable host.”

Pdf of first page of article

Link to journal article

Assorted awesome figures below:

September 22, 2011

Tree made with blood vessels.

By boojumsan via Flickr