With this important piece over at the Globe and Mail, it seems timely to reprint this commentary I wrote and published over at Chris’ Intersection Discover blog (May 3rd). Don’t even get me started on the pipeline business…

– – –

Why the Harper Majority is a Step Back for Science – Let Us Count the Ways

By DAVID NG

In case you missed it, last night saw the Canada election deliver a Conservative majority. It was aninteresting and historic vote for a variety of reasons, but the bottom line is that now the Harper government is in a position to do pretty much as it pleases, given its position of majority power in both the House of Commons and the Canadian Senate.

As is the norm for any democratic action, this is good and bad depending on your perspective and ideals. Those who make their homes in the business or economic front generally see the result as a positive; whereas those who value fairness, ethical government practices, and social issues tend to look upon the election as a daunting and frustrating setback. In this mix, however, is the scientific point of view. And speaking as a Canadian scientist, I want to use this space to make the case that all things being considered, this is a fundamentally bad moment in history for Canadian science.

To do this, let’s access how the Harper government (not the “Government of Canada” as it was once officially called) has performed so far (in the science context anyway).

And let’s argue for this in a rational way. We are after all scientific folk. In fact, let’s apply the good old rubric of looking at the claim, providing a reason, and then presenting the evidence for this stance.

First up is our claim: let’s just go with something direct:

The Harper Government is bad for Science.

As for coming up with a reason, it’s actually fairly straightforward. Here, we’ve seen repeated examples that would demonstrate a clear lack of understanding science culture, as well as actions that often undermine the very notion of scientific literacy. Sometimes, you get the sense that science just isn’t important to this government, and on occasion it even feels downright inconsequential.

But, of course, this wordy reason can’t stand on its own verbiage. We need concrete evidence for our claim, and to do this, it’s probably easiest to focus on a number of key points that demonstrate Harper’s modus operandi.

Point 1. The Harper government is not terribly scientifically literate.

There’s a few examples of this (also see point 2), but let’s simply draw attention to the appointment of a Minister of Industry, Science and Technology who waffles on the science of evolution. In case you don’t know his name, it’s Gary Goodyear: and in essence, his role in government is meant to be the primary driver on pushing and representing how science is funded, courted, guided, and basically done in Canada. Although an architect of many a cut to science funding in times that arguably need more scientific innovation (see 4 for more), he was and still is noted as a controversial figure when in 2009, the Globe and Mail asked him to share his stance regarding evolution. To this, he replied, “I’m a Christian, and I don’t think anybody asking a question about my religion is appropriate.”

Now from a scientific point of view, this type of statement is mildly troubling – you would hope that at least the Minister representing science would have more eloquent words to say on this subject. Unfortunately, this wasn’t the case as illustrated with his further comments on the matter when pressed again during a television interview. During this incident, he chose to proclaim his belief in evolution, but continued with this very odd and ludicrous description of what evolution is:

“We are evolving, every year, every decade. That’s a fact. Whether it’s to the intensity of the sun, whether it’s to, as a chiropractor, walking on cement versus anything else, whether it’s running shoes or high heels, of course, we are evolving to our environment.”

2. The Harper government has managed to make Climate Change science an ideological issue.

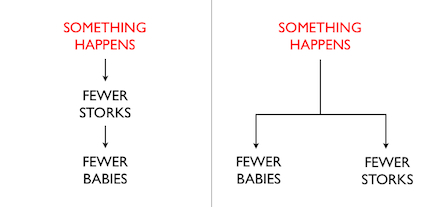

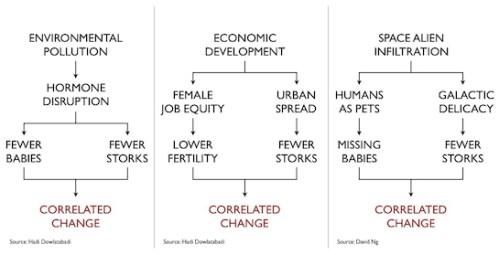

You’ve actually seen a lot of this already in American politics, but nowadays there’s also a Canadian version. Here’s how it works:

In general, science is fairly particular about the way it is done. The method is built to thrive on objectivity and it is ultimately based on the things we see, record, and analyze. It isn’t perfect, since the concept of a paradigm can exert influence, but the evidence it builds on still has to meet some pretty tough criteria – certainly much more stringent than other epistemologies, or other ways of knowing. Put another way, scientific evidence is not suppose to be swayed by ideological or partisan lines.

Despite this, Harper’s politics have warped the science of climate change into one of partisan debate. All other Canadian political parties take the science at face value, and build from it. Not so with the Conservatives. This is inherently disrespectful to the scientific community, as it suggests that we can make decisions concerning climate change in a place where scientific literacy has no currency, whereby the overwhelming scientific consensus is treated as nothing more than an interesting and suspicious footnote.

As a result, Harper runs the country on the pretense of whether one can trust or distrust the scientific evidence, without actually debating the actual technical strengths and weaknesses of the climate science data currently presented. Harper runs the country based on messages that economically sound promising, but are environmentally unsustainable, and have strong repercussions which conveniently will take form long after he is retired. Above all, he places an emphasis on nurturing a subtle form of climate change denialism and has made it part of the conservative ideology. From a scientist’s point of view, this is probably not the best way to formulate important policies – on “feelings” as oppose to concrete evidence. In essence, we can say that I may not be a betting man: but if I was, I’m pretty sure that the scientific community is the best place to get our odds.

Now, one might argue that this is not Harper’s stance at all. It would appear that the official take would proclaim the government’s official backing of the “fundamentals of climate change science.” However, as always is the case, actions speak louder than words. As evidence of this, you only need to keep track of the Harper’s record on climate change. Since obtaining its first minority government in 2006, the Conservatives have essentially moved away from Canada’s commitment to Kyoto, and has repeatedly undermine climate change talks (to the point of being consistent winners of the “Fossil of the Day” award), part of which involves the continual setting up of disappointing emission targets.

In 2009 the goal was to cut carbon emissions by 20% below 2006 levels by 2020; an equivalent of 3% below 1990 levels by 2020. The goal was later changed in early 2010 to 17% of 2005 levels by 2020; an equivalent of 2.5% above 1990 levels.

The three most populous provinces disagree with the federal government goal and announced more ambitious targets on their jurisdictions. Quebec, Ontario and British Columbia announced respectively 20%, 15% and 14% reduction target below their 1990 levels while Alberta is expecting a 58% increase in emissions. (Wikipedia, April 2011)

More troubling, is that Harper appears to not have any qualms about pushing his agenda in any way possible, and does so in a way that draws clear distinctions between party lines. In particular, is his flagrant misuse of Senate power to go against the democratic passing of a Climate Change Bill (Bill C-311).

Here, a quick lesson in Canadian government procedures might help. Essentially, when Canadian laws or Bills are put on the table, they need to go through a vote in the House of Commons. This is represented by elected members of government, such that the voting here is inherently meant to represent the “will of the people.” However, if passed, the law then needs to go through the Canadian Senate. This level of government is suppose to reflect a place of “sober second thought,” but historically, the Senate very rarely goes against the decisions made in the House of Commons. This is because Senate members are appointed, and therefore in principle are there to still respect the democratic underpinning of the House of Commons’ vote. However, in December 2008, Harper filled 18 vacant Senate spots with Conservative appointments, and has used this Senate majority in undemocratic ways – including the killing of the Climate Change Bill.

Still, there are other ways to force an ideology along: which brings us to point number three.

3. The Harper government has demonstrated a willingness to “muzzle” science.

In 2010, the release of Environment Canada documents showed that new media rules introduced by the Harper Government in 2007, with the aim to control the ability for Federal climate scientists to interact with media, had been responsible for what many of these scientists have called a “muzzling” effect.

“Scientists have noticed a major reduction in the number of requests, particularly from high profile media, who often have same-day deadlines,” said the Environment Canada document. “Media coverage of climate change science, our most high-profile issue, has been reduced by over 80 per cent.”

The analysis reviewed the impact of a new federal communications policy at Environment Canada, which required senior federal scientists to seek permission from the government prior to giving interviews.

The document suggests the new communications policy has practically eliminated senior federal scientists from media coverage of climate-change science issues, leaving them frustrated that the government was trying to “muzzle” them. (Montreal Gazette, March 15, 2010)

This facet of Harper’s strategy is especially troubling. Science, as a whole, is a venture that best works when there is fluidity and an openness in how information is shared. Whether that is within the scientific community in the form of expert peer review, or back and forth between scientists and the general public or the policy makers as a dialogue of civic consequence, there is simply no commendable reason for this form of control. It should be obvious that discussions on Climate Change, which has obvious public importance, things shouldn’t be run like a corporation protecting its secrets and/or hiding information that veers away from the desired message.

4. The Harper Government is out of touch with science culture: scientists are driven by many things, and not always by the industry/business/corporate mentality.

Over the last couple years, we’ve seen examples where the Harper Government has consistently pushed research towards a heavy emphasis for applied sciences and industry, often at the expense of basic science. Whether this is via funding cuts to granting agencies such as the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (a bastion of basic science research), diverting such monies towards projects where business-related objectives are encouraged, or via restructuring of the National Research Council such that industry-related projects are given priorities, there’s definitely a method to his ways. Overall, this indicates a general ignorance of how scientific progress works – that is, it is almost always the discoveries born from basic research that fuel the future innovation necessary for applied benefits. Put another way, if Harper continues on this track to give himself quick political gain, he does so at the expense of future Canadian science. Even a small lull in basic research in the present could result in a significant lull in applied and economic potentials in the future.

As well, this constant patronage towards the business side of science also doesn’t necessarily reflect the intentions of the scientists themselves. Money and economics may be desirable things for scientists, but most often there are other stronger motivations at stake – including an aspiration to bring about positive change in the world, as well as plain old intellectual curiosity.

An example of Harper’s willingness to always give credence to the corporate line, is his Government’s poor handling of the recently diposed Bill C-393. Essentially, this is an episode where bad politics trumped good science. The good science in this case is the fact that there are very effective antiretroviral drug out there, which make HIV/AIDS a treatable disorder. Unfortunately, these are mostly priced too high for individuals in developing countries – countries where unnecessary death from HIV/AIDS is catastrophically high. The bad politics concerns a frustrating series of events that saw a Bill (C-393), designed to fairly and with monitoring facilitate production of generic drugs, get passed in the House of Commons (i.e. democratically given the green light); then was taken to Senate, where it was deliberately stalled for five days, in an atmosphere where misleading information provided by the pharmaceutical industry was being distributed to the Tory Senators; such that it was ultimately killed by default when the new election was called. The fact that the reason for this was ultimately because of the Harper’s Government willingness to patronize Big Pharma is extremely galling, especially when so many lives were literally at stake.

Conclusion

It’s important to note that science culture isn’t the only thing that drives a civil society. However, as a conduit for reasoned discourse and relevant information that affects local and global concerns, it’s obvious that science must not be taken for granted. Based on last night’s election results, we have every reason to worry about the Conservative majority, as the Harper Government has repeatedly demonstrated past activities that not only take science for granted, but treat it with a form of contempt. The Harper government has consistently ignored whatever sound utility the scientific endeavor can provide, and by doing so, has put the future of Canadian science at risk, as well as the elements of society that would have otherwise benefited from it.

In the end, this means that we must watch the actions of this Harper Government more closely; and to be vocal, to be active, and to do our best to hold them to account for their actions. Democracy has given Harper a mandate to govern as he sees fit, and for this there should be an element of respect as well as an element of opportunity. However, Harper should not forget that Canadian democracy is ultimately driven by the people of Canada. For that reason, I will be watching you closely. Scientists will be watching you closely. Canadians will be watching you closely.