The words of Carl Sagan, inspirational even in comic form. #beautifullydone

By Gavin Aung Than over at zenpencils.com (Go check it out – very cool idea)

By Gavin Aung Than over at zenpencils.com (Go check it out – very cool idea)

It would be very very interesting to use this to tag pseudoscience nonsense, as well as political speeches generally.

By the always talented David McCandless.

By DAVID NG

About five years ago, a colleague (Ben Cohen) and I decided to conduct a little online experiment. Essentially, we thought it would be fun to host a puzzle. This would involve the sequential release of some fairly bizarre pictures. The goal, of course, was to see if we could entice the denizens of the internet to play along – in other words, could they figure out what was the unifying connection between all of these strange things that they were seeing?

The formal start to this process involved the presentation of three images (shown above). This included: (1) a gorgeous picture of a fish, specifically one drawn by Ernst Haekel; (2) a picture of a robot masquerading as a cow masquerading as commentary on industry; and (3) the front cover of an Elvis Presley VHS tape (remember those?) called “It Happened at the World’s Fair.” We then gave this whole exercise the snazzy title, PUZZLE FANTASTICA, which was the sort of thing that precariously walked that strange line where it was simultaneously awesome and stupid. Next, we added the tag line, “Do not click unless you are of reasonable intelligence,” and then we basically just sat back and waited [1].

What happened next was pretty amazing. Immediately, we got a lot of feedback and a lot of attempts at solving the puzzle. And, I should add, a lot of it was very sophisticated and, well, remarkable. But despite this ingenuity from our readers, Puzzle Fantastica did not get solved.

And so, we released another clue… and then another. The fourth clue was a short movie of someone’s lawn covered with a few of those plastic climbing things that one purchases for small children, as well as about 100 European Starlings mulling through that same patch of grass. The fifth was some text, about a hundred words, which read as if it was the start of a strange children’s novel.

For each of these new clues, we saw new wonderful attempts at solving the puzzle, which interestingly enough, were often modifications of previous attempts. We also saw a huge increase in the number of participants, significantly fueled by traffic from other websites [2]. By the end of the exercise, we had managed to court several hundred different answers for our puzzle. However, despite this outpouring, none of these fine attempts had found the “official” answer.

Still, we were so impressed with the effort and the diversity of what we saw, that we made a fancy graphic of the totality of solutions presented to us.

Click on image to see larger version.

As well, at the time, Ben and I were a little worried. When all was said and done, we realized that when we put up our “solution” (a play on the word CLONE), we would also need to recognize the fact that many of the readers’ answers were far more elegant.

Still, the whole process was sublimed. It was in many ways, a microcosm of the scientific method in action. What happened was that folks “saw something interesting” (our clues), and then they tried to fathom from these observations, a reasonable “reason why?” In other words, they were coming up with hypotheses: and their manner of testing them was waiting to see if the next clue would support or contest them. The participation was truly brilliant, and it was a testament to how creative a person’s mind can be, when driven to the prospect of trying to understand something mysterious. It was also turning into a great analogy that we could use for teaching purposes: “Look, it’s like the scientific method!” we both said.

Except that the analogy had one completely mind boggling, over-the-top, truly delicous kink, which actually made it all the more richer. You see (and here’s the thing): in truth, there was no solution.

That’s right. The whole puzzle was, in actual fact, a complete ruse. We were simply interested in seeing how a community can seemingly find wonderfully intelligent ways to connect odd disparate observations. And it worked like a charm. Too well, actually: we hadn’t expected such large numbers of participants which was a little stressful and also the reason why we decided to fabricate a answer that fitted but also one that hadn’t already been mentioned. It was as if we were forcing ourselves into a paradigm of sorts.

Which is fitting given what paradigms are in the world of scientific discourse. Here, Thomas Kuhn, the American Historian and Science Philosopher, famous for the publication of “The Structure of Scientific Revolutions,” says it best. He wrote that science “is a series of peaceful interludes punctuated by intellectually violent revolutions.” Furthermore, it is during those revolutions where, “one conceptual world view is replaced by another.”

What he was referring to was the idea that scientific discovery tends to work within paradigms. This is where there is an existing framework of knowledge that comfortably guides how observations are made, questions are asked, and how hypotheses are formed. However, history has also shown that on very rare occasions, these paradigms can change, and because they are so fundamental, such change can seriously rock the boat. We’re talking the Sun being at the center of the Solar System not the Earth; Einstein’s work on relativity over Newtonian physics; Darwin’s Natural Selection over all of that God stuff.

Our Puzzle Fantastica, admittedly by accident, actually illustrated how consequential a paradigm shift can be. In that our participants would have obviously acted in a completely different manner and would have provided completely different responses, had they known that there was never an answer in the first place. That particular change in our framework of knowledge for the puzzle was, suffice to say, revolutionary.

I bring this up, because it is yet another part of the scientific method. It is in many ways, the ultimate example of why Popper’s “You can’t ever prove the Truth” statement is so important. You just never know. Paradigm changes are actually implied with our scientific method flowchart, except without the intensity. In fact, it might be worth changing our flowchart to reflect this:

1. See something.

2. Think of a reason why.

3. Figure out a way to check your reason.

4. And? (very very very rare chance of a WTF in font 100 times larger!)*

5. Now, everyone gets to dump on you. (people actually freaking out!)*

6. Repeat, until a consensus is formed.

(* these grey bits refer to this paradigm business).

So there you have it: The scientific method in all of its glory. Although, hopefully, after reading through this material, you realize that this flowchart is still a gross simplification. Indeed, there are many who would prefer we not even call it the Scientific Method anymore. Instead, we should refer to it as the Scientific Process [3], as a way to highlight its fluidity and nuances, and that the flowchart should probably look a lot more busy and complicated with many criss crossing lines.

I personally like all of these , with maybe a secret desire to introducing a new term, Modern Baconian Method [4] – but that is just me. What might be most important from of all of this, is to just “get it.” It is just for everyone to have a certain degree of familiarity on how science can provide us with knowledge, and how that knowledge came to be.

Why? Because when you do, you’ll finally understand why the usual way we get our scientific information – that is, television, newspapers, the web and the like – is often completely fucked up.

NOTES

[1] Puzzle Fantastica #1: “Fish-Cow-Elvis” [do not click unless you are of reasonable intelligence]. Scienceblogs.com. (Assessed January 7th, 2012)

[2] Introducing Puzzle Fantastica. Boingboing.net (Assessed January 7th, 2012)

[3] Like these folks at Understanding Science.

[4] The Baconian Method, referred to earlier in part 1, is described here.

(3rd draft)

By DAVID NG

On a cold and miserable evening sometime during the fall of 2006, I found myself sneaking into a 4 star hotel and gate crashing an international science philosophy conference. Yes… I am that wild.

O.K. admittedly, this might not sound like the most thrilling of endeavours, and certainly not something that would beckon a Hollywood screen writer, but it was nevertheless quite exciting to me. Not the least of which was because this act of rebellion led to meeting a minor celebrity. This is someone, who if you took the time to google, you would discover in various photo-ops posing with folks as varied as Steven Pinker, President Jimmy Carter, and even Martha Stewart. As well, the word “posing” doesn’t actually do these photos justice: rather, these well known individuals are literally holding him up.

Specifically, the celebrity I’m referring to goes by the name of Prof. Steve Steve, and the reason why he is always held is because he is, in actual fact, a small stuffed toy panda. True, he not necessarily a well known celebrity, but, he is definitely an inspiration in certain scientific communities for reasons related to an interesting decade long battle of words.

Specifically, these words:

“We are skeptical of claims for the ability of random mutation and natural selection to account for the complexity of life. Careful examination of the evidence for Darwinian theory should be encouraged.”

The above is a statement crafted by the Discovery Institute, a Seattle based think tank that primarily acts as a front to push the concept of “Intelligent Design” into public school science curricula. This is essentially the idea that elements of life were consciously “designed and/or created” by something with intelligence (for instance, a God or a tinkering alien, etc). It is more or less a supposed counterpoint to the science of evolution.

Since the statement’s release in 2001, the institute has also maintained a list of signatories, who are collectively referred to as A Scientific Dissent From Darwinism[1]. In other words, this is a list of folks with advanced degrees who insist that evolution is a scientifically weak concept. As of December 2011, 842 signatures had been collected, and the Discovery Institute has often claimed that this exercise is evidence that evolution is, indeed, highly debatable as science; and that other views, specifically views that ultimately include intelligent design (and ergo creationism) should be entertained and validated within science education.

This, of course, is rather silly – if not altogether disturbing to those who are scientifically inclined. And so in response, the National Centre for Science Education (NCSE) decided to launch its own statement to counter this awkward pseudoscience babble. Released in 2003, this one read:

“Evolution is a vital, well-supported, unifying principle of the biological sciences, and the scientific evidence is overwhelmingly in favor of the idea that all living things share a common ancestry. Although there are legitimate debates about the patterns and processes of evolution, there is no serious scientific doubt that evolution occurred or that natural selection is a major mechanism in its occurrence. It is scientifically inappropriate and pedagogically irresponsible for creationist pseudoscience, including but not limited to “intelligent design,” to be introduced into the science curricula of our nation’s public schools.”

And like the other statement, signatures were courted, where as of April 25th, 2012, the total number had reached 1208 individuals [2]. Apart from the empirically obvious fact that the Scientific Dissent from Darwinism has fewer signatures, it is also worth pointing out two other significant differences between the two opposing lists.

First, many have questioned the credibility of the Discovery Institute signatures. For instance, some argue that over the years, the signatures have often been inconsistently attributed (many titles are vague, university affiliations may be absent, current involvement in scientific activity suspect), and often signatories were not necessarily aware of the agenda behind the vague statement [3]. In addition, one also notices that only a small proportion of them actually have relevant biology backgrounds. In fact, in an analysis done in 2008, this was calculated to be just shy of 18%. In contrast, the same analysis determined that the robustly labeled NCSE list scored a much higher 27% [4].

Still, it is the second difference that is most noteworthy (in fact, it’s also brilliant). This is where every signatory in the NCSE list is named Steve… Or Stephen, or Stephanie, or Stefan, or some other first name that takes it root from the name “Steven.” Yes, even Stephen Hawking is on the list. Put another way, the list would obviously be much much larger without this restriction [5].

This is why the NCSE list is also known as Project Steve (an affectionate nod to noted evolutionary biologist and author, Steven Jay Gould), and this was also why it was very exciting to meet with Prof. Steve Steve. You see – he is the project’s official mascot, and he is a great reminder of why it is important to invalidate those who would be inclined to create controversy around the science of evolution, be it for political or religion reasons.

He is also a lovely reminder of the importance of another aspect of the scientific method. Specifically, this concerns the part where everyone gets to dump on you, or perhaps more accurately, the part where everyone – who’s an expert – gets to dump on you. It refers to the idea of how “proof” is accessed and validated. In science terms, we call this part of the method, “expert peer review.”

This is important because it dictates that scientific knowledge gets to be critiqued in a very particular manner. It gets examined in such a way, where one is left with a scientific opinion that:

(1) is based on the examination of tangible evidence, which is not only made publicly available for all to see, but is also described in enough excruciating detail so that anyone has the option to try to reproduce it (hence the existence of peer reviewed journals);

(2) is formulated by those who actually know what the hell they are talking about;

(3) is backed by the most numbers of people who actually know what the hell they are talking about; and

(4) did I mention the bit about people actually knowing what the hell they are talking about?

In other words, this idea of expert peer review is really really a good way of critiquing evidence and thereby evaluating the claims and the hypotheses they contend to support. Moreover, it is especially important because it provides a mechanism for general society to check things out – since not everyone in society has the necessary background to evaluate scientific claims and evidence. For instance, a non-geneticist may be hard pressed to fully assess DNA sequencing data; a non-computer scientist may be hard pressed to appraise the relevance of a climate model – but that’s o.k. since this is what expert peer review is set out to do. It sets out to gather the required community of scientists to check things out for you.

Such a review process is all the more pertinent because the reality is that it’s not that difficult for anyone to be convincing and still disingenuously utter the phrase, “and we have proof!” A Scientific Dissent From Darwinism is a good example of this. Which is why the rational protect themselves from such scams by relying on these communities of experts, who in turn are vested in the scientific method, and who strive to objectively and publicly analyze such sentiments for validity.

Which is to say, that clearly, the list of Steves win hands down.

Me (and Janet, John, John, and Ben) with Prof. Steve Steve at an international science philosophy conference.

– – –

NOTES:

[1] A Scientific Dissent from Darwinism. (Assessed January 7, 2012)

[2] Project Steve Website. (Assessed January 7, 2012)

[3] Doubting Darwinisms Through Creative License. (Assessed January 7, 2012)

[4] Project Steve: 889 Steves Fight Back Against Anti-Evolution Propoganda. Science Creative Quarterly. (Assessed January 7, 2012)

[5] For instance, on quick examination of the December 2011 edition, there are 10 individuals on the Dissent list who names would fit under the Project Steve criteria (all Stevens or Stephens). Given that this represents 1.19% of all the names on that list, we could then, by analogy, project that the NCSE could have easily produced a list of close to 100,000 names, had they not included the name restriction.

(3rd draft)

Instead, speak up. Seriously, we all know that most of the noisy ones out there are very disappointing (scientifically).

Via xkcd.

perpilocutionist

n. one who expounds on a subject of which he has little knowledge

(via futility closet)

By DAVID NG

(I always thought that this piece would have been great as a pictorial. First published at McSweeney’s)

– – –

1.

Hydrochloric-Acid-Filled Piñatas

Good: Have the sturdy construction required to ensure no unintended leakage of contents.

Bad: Possible severe burning. Brings the party down.

2.

Endangered-Animal Piñatas

Good: Kids love animals. High potential for very cute-looking piñatas, like baby seals, for instance.

Bad: Beating with a stick sort of sends the wrong message.

3.

Particle-Accelerator Piñatas

Good: Built full-scale and often several miles in dimension. Therefore, young children find them easy to hit.

Bad: Each one worth several billion dollars. Parents generally not keen on damaging them.

4.

Smallpox (Variola major) Piñatas

Good: Cool virus shape.

Bad: Highly contagious and high mortality rate. Would also bring party down—as well as everyone else within a 100-mile radius.

5.

Infinity-Symbol Piñatas

Good: Possibly a way to address the often reported decline of mathematics education.

Bad: Thinking about infinity makes my head hurt. Now imagine having to explain it to a child over and over again.

6.

Piñatas in the Shape of the USA and Filled

With the Greenhouse Gas Carbon Dioxide

Good: Sort of works as a metaphor for the United States’ role in the global-warming crisis.

Bad: Unfortunately, the irony would be totally wasted on a 5-year-old.

By DAVID NG

“You see something interesting…”

This little phrase is often the start of the scientific process. In that it all begins when someone, possibly you, has noticed something intriguing. This doesn’t mean that it has to be interesting to everyone – just as long as it’s interesting to someone. In fact, sometimes, the science will stop right there. In other words, the act of just “observing” might be good enough – think about how everyone would feel if you were the first to discover a certain kind of creature.

Still, most conventional views of science would assume that you’ve seen something curious enough to merit the question “why?” And it is in that inspired act of asking a question, where arguably the most important part of the scientific method takes form.

We are, of course, referring to the notion of the hypothesis: which according to the Oxford Dictionary is defined as:

“A supposition or proposed explanation made on the basis of limited evidence as a starting point for further investigation”

For us, in less eloquent terms, we say that this is the part where you try very hard to “think of a reason why.” Furthermore, when you do this, you inadvertently set the scene for the next stage of the method by defining how a person might “figure out ways to check your reason why.” To a scientist, this last phrase is a colloquial way of talking about experiments.

For fun, let’s explore these concepts by using an example. Here, we’ll focus on some interesting observations that were noted in China during the early 1980’s. Essentially, what folks observed was that there was a discernable decline in Chinese stork numbers [1]. As well, there was also a drop in fertility rates [2]. In other words, storks in China were disappearing and the Chinese appeared to be having less babies.

But why?

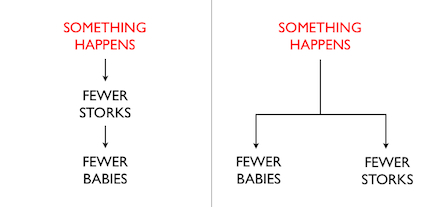

At one level, we might suppose that the two are not at all related. It could simply be a correlation and nothing more. But for the purposes of our discussion, let us suppose that we are trying to surmise whether the two are ultimately connected – whether there was truly a causative element involved.

Here, some of the hypotheses might assume that there is a continuum involved, in that one of the observations is actually directly responsible for and logically leads to the other observation. For instance, if we play into the stork/baby mythology, where storks do indeed deliver babies, perhaps we can say that the decline in stork numbers was in turn causing the baby effect. Others, however, might ponder whether there is a more central reason for the two trends. In this case, we might talk about a hypothesis that suggests one prominent thing at play that is simultaneously responsible for both outcomes.

Here, we can try to distinguish the two scenarios by looking at the evidence more closely. Does the stork decline happen before or after the baby decline? What exactly are the numbers associated with the declines? Important, because even with the drop taken into account, the actual numbers of storks might still be more than enough to cover the number of babies born. In any event, as you can see, a hypothesis can be quite nuanced and is really only a small step in a much longer path.

For amusement’s sake, let’s take this idea of nuance even further and look at the three potential hypotheses presented below [3]. Here, they all focus on a core reason (environment, economics, or aliens) that could explain our observations.

Looking at these flowcharts more carefully, you can see that when accessed logically, they all work. Even with the somewhat interesting inclusion of aliens, the fact remains that all three could be considered acceptable, worthy even. However, this is very different from a hypothesis being valid. Validity, which aims to make sure that what you say is indeed true, or at least true under every logical interpretation, is a much higher bar to meet. It is something that needs to be earned through the critical examination of evidence.

Now this is an especially important word, so we’ll once again invite the gravitas of the Oxford Dictionary to provide a definition:

“Ground for belief; testimony or facts tending to prove or disprove any conclusion.”

But such grounds can take several different forms, constituting strong or weak evidence. If we focus on the alien claim in particular, evidence might look a little like this:

1. We found an alien! And we have proof!

Here, we have important evidence from the point of view of addressing one critical question: are aliens real? It is crucial because it could be said that this detail is a major stumbling block in the alien hypothesis. However, proof of the existence of aliens isn’t in of itself strong evidence to support the hypothesis. This is because it doesn’t address any of the specific ideas and mechanisms put forth to explain our stork and baby narrative. Ideally, you would want to see data that demonstrated the involvement of our said alien with either storks or babies – actually, you would like to see both.

2. We found an alien eating a stork! We also found an alien with a baby on a leash! And we have proof!

This type of evidence is better, but it is still technically weak. This is because just having this data isn’t necessarily conclusive. What if the stork you see is, in actual fact, American? What if the pet baby is not Chinese? What if it is Chinese, but not in fact, from China? What if it is a result of alien cloning techniques? As you can see, the scientific mind will take what might otherwise appear convincing, and deconstruct it skeptically. A scientific mind will continually probe, and continually look for flaws in the evidence.

3. We found an alien eating a stork, and we have biochemical proof that the stork is from China! We found an alien with a pet baby, and we even saw the alien take the baby from a family in China! And we have proof!

Now, we’re getting closer, but now the issue is in the matter of whether this evidence represents an impactful occurrence. In other words, this particular data is really only good for showing the loss of one stork and of one baby. Obviously, this can hardly validate the observation that whole populations have dropped, which means that better evidence would also provide a better sense of the numbers involved. This particular stork and this particular baby could represent a simple coincident. Furthermore, what if this data was flawed for other reasons? Perhaps, if we had decided to observe the baby a little longer, we would have noticed that the baby was in fact being kept for food! This doesn’t change the fact that aliens may still be responsible for the drop in numbers, but it does nevertheless alter the sentiment of the current hypothesis significantly.

Of course, this type of review can go on and on. And the thing is: it does. What we have here is this continual cycle of coming up with hypotheses, coming up with ways to address the hypotheses, coming up with evidence, and then reevaluating everything over and over and over again.

Hopefully, you can see why this can very easily become an arduously slow process, although that’s not to say that it is always slow. More importantly, you should be able to appreciate how the process can lead to varying outcomes. It could lead to revisiting old ideas. It could naturally result in conflicting views. It could even cause your explanation (and also possibly the scientific discipline) to change directions dramatically. Imagine, if you will, that the real answer to our stork and baby scenario was a little bit about everything – a little mythology, a little environment, a little economics, and even a little bit about aliens. If this were the case, you could probably appreciate how difficult that complete story might be to tease out.

Here’s another thing to note: if you think about this process carefully, you will soon realize that the continual acquiring of scientific evidence never actually proves anything to be one hundred percent certain. It can only modify or support an existing hypothesis, although by supporting it relentlessly, a hypothesis can get stronger and stronger and perhaps one day rise to the rank of a scientific theory or scientific law. But even there, there is no certainty that there won’t be something that comes along to discredit that idea in a single stroke. This is Karl Popper’s take on the philosophy of science: that at the end of the day, you cannot prove something to be true: you can really only prove something to be false. This might take a moment to ponder, but if you do so with our alien example, you’ll note that this description does fit.

On the whole, our little alien discussion hopefully provides a window into how the scientific method works. But if we are honest with ourselves, we should also admit to glossing over something very important. Specifically, it’s in the parts where we have very nonchalantly uttered the phrase, “And we have proof!”

This bit, we will spend some more time on in the next section, as it considers how we distinguish strong evidence from weak evidence. Which is all the more daunting these days, since it’s quite likely you might not even understand the technical details of the evidence. Indeed, it might even be completely alien to you.

Notes:

1. Ma, Ming; Dai, Cai. “The fate of the White Stork (Ciconia ciconia asiatica) in Xinjiang, China”. Abstract Volume. 23rd International Ornithological Congress, Beijing, August 11–17, 2002. p. 352.

2. S Horiuchi. “Stagnation in the decline of the world population growth rate during the 1980s.” Science 7 August 1992: Vol. 257 no. 5071 pp. 761-765

3. Pollution and economic scenarios via personal communication with Hadi Dowlatabadi.

(3rd draft)

“Mn, Na, Mn, Na… Ba, D, P, D, P…”

I was challenged by some friends to see if I could include the below video in a public talk I had to give last week on science literacy.

I think I succeeded. I used it as a prelude to demonstrating that Chemistry, and the physical sciences generally, are freaking everywhere. p.s. A warning: the video is AWESOME, but it will live in your head for at least a week if you play it.

A little bizarre really. It will be interesting to see how folks react to this: there’s already an amusing comment thread on reddit.

Via Fresh Photons.

Via collinscomics.com. Click on image for larger version.

From the great Scenes from the Multiverse, via Boing Boing.

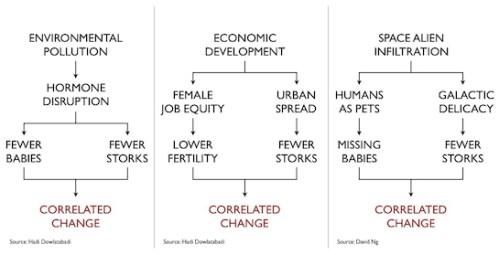

This is a wonderful way of encapsulating how some in the general public misinterpret science stories. i.e. correlation and causation is not the same thing.

By DAVID NG

Today, I feel like doing a plant – no, an animal. Yes, today, I am going to make an animal. And it will be a masterpiece. I shall call it the…. No wait! Maybe I should think of the name later. Yes, you should always name your pieces after you have completed them. Better that way.

OK then. An animal it is. More specifically, a vertebrate. Large body, four legs, one tail, one head, usual stuff on the head – i.e., let’s just follow the standard animalia rubric. Nothing exciting there. Not yet anyway. So let’s give it an armored tail, with poisonous tendrils and a stink that can kill. Oooh, I like that – but maybe it’s too much. Why such a fancy tail? Maybe the tendrils can come out of its nostrils (note to self: Have I designed nostrils yet?). And the stink can come from the body itself.

But it doesn’t quite feel right. Feels forced. No matter, I suppose I can simply start over. Besides, I did the poisonous tendrils last week. But keep the stink? Yes, let’s keep that.

I know. How about we give it three, no eleven, no four stomachs! Four stomachs! For the efficient eating, of the grass. I am truly inspired! Don’t stop there. How’s this? This animal should urinate milk. From its groin, no less. From little appendages which I will humbly call teats that collectively, communally, reside on a mound of tissue I will call a brother.

Now I am on a roll. Milk will flow from the teats of this animal’s brother.

No wait, I cannot call it a brother. This animal has no lips – don’t want it to have lips – too common a thing for a masterpiece. Seen that, done that, yesterday’s news. But you can’t say the word “brother” without lips. Poor animal, that would be cruel. Instead, let’s call it an udder. Yes, an udder – that’s much better.

Now, of course, I need to work in a clown somehow. I love clowns. In truth, clowns are my all-time favorite design. How will I do this? Perhaps give the animal a raucous and overt sense of humor? Make it wear funny shoes? Make it scare the shit out of young children? No, not subtle enough – I want this animal to be so much deeper than that.

What if, and I’m just saying things as they come to me, this animal-can-be-ground-and-shaped-into-a-meat-patty- which-can-be-mass-produced-and-fried-on-heating-elements, and-then-sold-by-a-corporate-entity-bent-on-feeding-the-obesity-line-to-young-children -by-using-as-their-public-representation-and-symbol, a-clown, whom-we-shall-call-Jesus (no-wait,-let’s-save-that-one-for-later), whom-we-shall-call-Ronald-McDonald, and-these-meat-patties, which-will-be-inexplicably-and-mysteriously-called-hamburgers -after-a-completely-different-animal-I-haven’t-created-yet, will-also-be-considered-sacrilegious-by-fully-one-sixth-of-the-world’s-population, and-oh-oh-why-is-it-that-the-numbers-0157-cry-out-to-me? because-OH-MY-GOODNESS-I-can’t-believe-it, but-this-stuff-is-just-so-brilliant!

…

Take a breath. WHheeeew-hooooooo. Calm down. That’s pretty good. But maybe just think about some of the simple things now. Like color. Yes, color is good. And easy – let’s go with the rustic look, plus spots. Et voilà. We have finished yet another creation, which for some reason, I feel inclined to call a cow. Hold on, one last thing. It shall go “moo” when it speaks. Yes, that’s a nice touch, even if I do say so myself. People are sure to talk about that one, maybe even create a song or two.

Originally published at Inkling Magazine.