Nikola Tesla letterhead: the subdued and EPIC versions.

This is what he used c:1900:

Then, in 1911, he apparently had something like this:

There is, I bet, a great story in this somewhere…

From letterheady.

This is what he used c:1900:

Then, in 1911, he apparently had something like this:

There is, I bet, a great story in this somewhere…

From letterheady.

By Gavin Aung Than over at zenpencils.com (Go check it out – very cool idea)

Dr. Sara Josephine Baker: look her up. Under her watch the infant mortality rate in New York city went from being one of the worst possible to one of the most enviable, and her ideas on public health and preventative care spread far and wide. She swam against the stream her entire life and she saved thousands of people, what more do you want in a hero?

By Kate Beaton. More on Dr. Baker at wiki.

Men and Machines, Dazed and Confused

Portrait of Charles Darwin

“Critically Endangered”

Barracuda

Lots more to see at Sarah’s portfolio site.

In 1800, as the result of a professional disagreement over the galvanic response advocated by Galvani (he of the electricty twitching frog leg’s fame), he invented the voltaic pile, an early electric battery, which produced a steady electric current.[6] Volta had determined that the most effective pair of dissimilar metals to produce electricity was zinc and silver. Initially he experimented with individual cells in series, each cell being a wine goblet filled with brine into which the two dissimilar electrodes were dipped. The voltaic pile replaced the goblets with cardboard soaked in brine. The battery made by Volta is credited as the first electrochemical cell. (via wiki)

Note that Volta is also the first to characterize the gas Methane. In fact, he even devised an air gun contraption that relied on igniting the flammable gas (see this link for pictures). For this and his battery invention, he was made a count by Napoleon.

Many library collections use special equipment, such as special gloves and climate-controlled rooms, to protect the archival materials from the visitor. For the Pierre and Marie Curie collection at France’s Bibliotheque National, it’s the other way around.

That’s because after more than 100 years, much of Marie Curie’s stuff – her papers, her furniture, even her cookbooks – are still radioactive. Those who wish to open the lead-lined boxes containing her manuscripts must do so in protective clothing, and only after signing a waiver of liability.

.

.

Via Christian Science Monitor. Image from Wiki.

That’s it… I need a radical change in hairstyle.

From

Wallace’s Condensed Primordial Soup is made from Earth-grown organic ooze and a special blend of prebiotic compounds. For four billion years Wallace’s recipe has remained the same with hundreds of amino acids, no artificial life, no MSG added, no cholesterol and no regrets. Later life forms love it!

For sale and via 826DC. Note that Wallace is in reference to Alfred Russel Wallace.

By DAVID NG

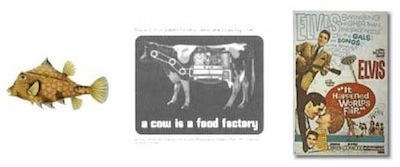

About five years ago, a colleague (Ben Cohen) and I decided to conduct a little online experiment. Essentially, we thought it would be fun to host a puzzle. This would involve the sequential release of some fairly bizarre pictures. The goal, of course, was to see if we could entice the denizens of the internet to play along – in other words, could they figure out what was the unifying connection between all of these strange things that they were seeing?

The formal start to this process involved the presentation of three images (shown above). This included: (1) a gorgeous picture of a fish, specifically one drawn by Ernst Haekel; (2) a picture of a robot masquerading as a cow masquerading as commentary on industry; and (3) the front cover of an Elvis Presley VHS tape (remember those?) called “It Happened at the World’s Fair.” We then gave this whole exercise the snazzy title, PUZZLE FANTASTICA, which was the sort of thing that precariously walked that strange line where it was simultaneously awesome and stupid. Next, we added the tag line, “Do not click unless you are of reasonable intelligence,” and then we basically just sat back and waited [1].

What happened next was pretty amazing. Immediately, we got a lot of feedback and a lot of attempts at solving the puzzle. And, I should add, a lot of it was very sophisticated and, well, remarkable. But despite this ingenuity from our readers, Puzzle Fantastica did not get solved.

And so, we released another clue… and then another. The fourth clue was a short movie of someone’s lawn covered with a few of those plastic climbing things that one purchases for small children, as well as about 100 European Starlings mulling through that same patch of grass. The fifth was some text, about a hundred words, which read as if it was the start of a strange children’s novel.

For each of these new clues, we saw new wonderful attempts at solving the puzzle, which interestingly enough, were often modifications of previous attempts. We also saw a huge increase in the number of participants, significantly fueled by traffic from other websites [2]. By the end of the exercise, we had managed to court several hundred different answers for our puzzle. However, despite this outpouring, none of these fine attempts had found the “official” answer.

Still, we were so impressed with the effort and the diversity of what we saw, that we made a fancy graphic of the totality of solutions presented to us.

Click on image to see larger version.

As well, at the time, Ben and I were a little worried. When all was said and done, we realized that when we put up our “solution” (a play on the word CLONE), we would also need to recognize the fact that many of the readers’ answers were far more elegant.

Still, the whole process was sublimed. It was in many ways, a microcosm of the scientific method in action. What happened was that folks “saw something interesting” (our clues), and then they tried to fathom from these observations, a reasonable “reason why?” In other words, they were coming up with hypotheses: and their manner of testing them was waiting to see if the next clue would support or contest them. The participation was truly brilliant, and it was a testament to how creative a person’s mind can be, when driven to the prospect of trying to understand something mysterious. It was also turning into a great analogy that we could use for teaching purposes: “Look, it’s like the scientific method!” we both said.

Except that the analogy had one completely mind boggling, over-the-top, truly delicous kink, which actually made it all the more richer. You see (and here’s the thing): in truth, there was no solution.

That’s right. The whole puzzle was, in actual fact, a complete ruse. We were simply interested in seeing how a community can seemingly find wonderfully intelligent ways to connect odd disparate observations. And it worked like a charm. Too well, actually: we hadn’t expected such large numbers of participants which was a little stressful and also the reason why we decided to fabricate a answer that fitted but also one that hadn’t already been mentioned. It was as if we were forcing ourselves into a paradigm of sorts.

Which is fitting given what paradigms are in the world of scientific discourse. Here, Thomas Kuhn, the American Historian and Science Philosopher, famous for the publication of “The Structure of Scientific Revolutions,” says it best. He wrote that science “is a series of peaceful interludes punctuated by intellectually violent revolutions.” Furthermore, it is during those revolutions where, “one conceptual world view is replaced by another.”

What he was referring to was the idea that scientific discovery tends to work within paradigms. This is where there is an existing framework of knowledge that comfortably guides how observations are made, questions are asked, and how hypotheses are formed. However, history has also shown that on very rare occasions, these paradigms can change, and because they are so fundamental, such change can seriously rock the boat. We’re talking the Sun being at the center of the Solar System not the Earth; Einstein’s work on relativity over Newtonian physics; Darwin’s Natural Selection over all of that God stuff.

Our Puzzle Fantastica, admittedly by accident, actually illustrated how consequential a paradigm shift can be. In that our participants would have obviously acted in a completely different manner and would have provided completely different responses, had they known that there was never an answer in the first place. That particular change in our framework of knowledge for the puzzle was, suffice to say, revolutionary.

I bring this up, because it is yet another part of the scientific method. It is in many ways, the ultimate example of why Popper’s “You can’t ever prove the Truth” statement is so important. You just never know. Paradigm changes are actually implied with our scientific method flowchart, except without the intensity. In fact, it might be worth changing our flowchart to reflect this:

1. See something.

2. Think of a reason why.

3. Figure out a way to check your reason.

4. And? (very very very rare chance of a WTF in font 100 times larger!)*

5. Now, everyone gets to dump on you. (people actually freaking out!)*

6. Repeat, until a consensus is formed.

(* these grey bits refer to this paradigm business).

So there you have it: The scientific method in all of its glory. Although, hopefully, after reading through this material, you realize that this flowchart is still a gross simplification. Indeed, there are many who would prefer we not even call it the Scientific Method anymore. Instead, we should refer to it as the Scientific Process [3], as a way to highlight its fluidity and nuances, and that the flowchart should probably look a lot more busy and complicated with many criss crossing lines.

I personally like all of these , with maybe a secret desire to introducing a new term, Modern Baconian Method [4] – but that is just me. What might be most important from of all of this, is to just “get it.” It is just for everyone to have a certain degree of familiarity on how science can provide us with knowledge, and how that knowledge came to be.

Why? Because when you do, you’ll finally understand why the usual way we get our scientific information – that is, television, newspapers, the web and the like – is often completely fucked up.

NOTES

[1] Puzzle Fantastica #1: “Fish-Cow-Elvis” [do not click unless you are of reasonable intelligence]. Scienceblogs.com. (Assessed January 7th, 2012)

[2] Introducing Puzzle Fantastica. Boingboing.net (Assessed January 7th, 2012)

[3] Like these folks at Understanding Science.

[4] The Baconian Method, referred to earlier in part 1, is described here.

(3rd draft)

Science history rocks! This is a picture of Percival Lowell. More at his wiki entry.

“The trouble with reading about a given woman’s history who was born before your mom is that sometimes, they were hilarious, powerful, tough, loud, et cetera et cetera all good comic making material! But then sometimes, man, the main thing about them is that they just got screwed, big time. I think when I read about Rosalind Franklin, or Mary Anning, or whoever, of just how shitty stealing someone else’s ideas really is. If I opened a newspaper and saw my comic in it signed by some random dude who was getting paid for it, I’d lose my cool! Dear readers, I would have an undignified tantrum. Wouldn’t you?” Kate Beaton

By the awesome Kate Beaton.

I love the back story to this:

“Much of Newton’s important work on calculus is developed in this large notebook, which he began using in 1664 when he was away from Cambridge due to the plague. Newton inherited the book from his stepfather, Rev Barnabas Smith, who used it from about 1612 to record his own theological notes (see, for example, his notes on adultery, in Latin). Newton was not interested in his stepfather’s jottings: its value to him was the large number of blank pages, which he began filling with his mathematical and optical calculations. Although the bulk of his work in this manuscript dates from the mid-1660s, Newton continued to use into the 1680s and possibly even the 1690s.” (link)

More of Newton’s papers at the Cambridge Digital Library

By Bob Dole, via “everywhere on the internet.”

“By Heidi Sandhorst

Famous Physicists 2010 Trading Card Set for sale. 20 4″ x 6″ glossy cards with rounded corners featuring handmade artwork and information about each physicist on the back as well as an inspirational quote from each physicist. Each set comes in a black box with hand drawn label and gold rubber band to hold it shut. $20 plus s+h (if applicable).

Email me at heidisandhorst@gmail.com if you are interested in purchasing a set.”

Via Fresh Photons.

Well… what’s not to love? Via Fresh Photons.

From the talented Kate Beaton, who has a number of wonderful pieces concerning greats in scientific history: so much so that I feel compelled to create a new popperfont category (science history). Oh yeah, and here’s the wiki link to Tycho Brahe if you’re curious (the assumption is that you know who Kepler is already, right?)