A picture of a see-through frog and her babies. #amazing

Via imgur.com.

By DAVID NG

Dear Sirs,

I know an omen when I see one, and it needn’t even involve a two-headed goat. As a scientist with a background in cancer research, the revelation I’m referring to is a bit of homework I did on the average yearly amount of money spent on programming by your television networks (about $1.5 billion). A number which strangely mirrors the average amount of money given last year to each of the 18 institutes within the National Institutes of Health, an organization that is the U.S.’s backbone of publicly driven medical research. Clearly, this is a call to merge the two enterprises together. So in the interest of public health, and given the pervasiveness of reality TV, I wish to expound to you four possible examples that demonstrate the feasibility of this union.

i. Real Science, Real People:

In the early 90s, studies were conducted whereby a single male mouse was presented with a plethora of different female mice. What was discovered was that the most desirable females had immune system genes that were most distinct from the male suitor. In other words, the female picked had a particular genetic background. Such a mechanism of mate selection would please Darwin since the offspring produced would inadvertently benefit from the most diverse, or most advantageous, immune system. More pressing, however, is the question of whether this decidedly unromantic notion pertains to mate choice in humans? Fortunately, we can now answer this question by asking the participants of programs like The Bachelor or The Bachelorette to provide a blood sample along with their video profile. This way, research can finally circumvent the sticky ethics of conducting such experiments on humans. On the plus side, this research opportunity should also generate its own built-in funding infrastructure as it can be easily applied to beat Vegas odds.

ii. Save Money:

Currently, every drug used for medicinal purposes in the United States needs to navigate through the strict and often precarious guidelines imposed by the Food and Drug Administration. This is an extremely long and expensive process, averaging 15 years and upward of $300 million in financing from discovery to product. Inevitably, most of this arduous process is due to the proper design and delivery of human clinical trials that examine drug efficacy and safety. Why not incorporate these trials into television shows like Fear Factor or Survivor? If contestants are willing to drink the seminal fluids of cattle or eat squirming maggots the size of your thumb, wouldn’t these same individuals revel in an opportunity to eat untested drugs? We could even have a “totally untested” and a safer “well, the mice survived” version of the same contest! In any event, millions of dollars would be saved.

iii. Promote Technology Development:

Medical research is largely driven these days by the ingenious design of equipment that can do new things or do old things better, faster, bigger, cheaper, safer. This to me is an invitation to incorporate medical technology development into reality TV. Why can’t Junkyard Wars showcase a competition to build the fastest DNA sequencer. Or viewers watch an episode of BattleBots that pits equipment used for insulin production. If Extreme Home Makeover can build a whole new environment in seven days, then why can’t you “fix that genetic mutation” in the same seven days. It’s no surprise that ingenuity often percolates under tough situations, and I can think of no tougher than a scenario where contestants only have 48 hours and a $1000 budget to meet their objective.

iv. Fostering Interest in Science Careers:

If we can have programming that features Donald Trump searching for a skilled apprentice, why can’t we use the same template to attract top graduate students. It should be simple enough to invite a feisty Nobel Laureate with an ego big enough to oversee the process. Just think of the entertainment value generated by having a team of young researchers told “Your project is to work together and come up with a cure for cancer in three days. And don’t forget—if you fail, you will meet me in the seminar room where somebody will be fired!” I mean, really—this stuff sells itself!

To conclude, I hope these four simple examples illustrate the opportunity at stake. It would be a great shame to not utilize these two great charges for the benefit of all. Now if we can only get the Food Network on board—maybe an episode of The Iron Chef with two-headed goats as the special ingredient?

Sincerely,

Dr. David Ng

Via Yankee Pot Roast, 2005.

“This video is a complete time-lapse video of the Sun spanning the entire months of September, October and November 2011 as seen through the SWAP ultraviolet instrument onboard the European Space Agency spacecraft Proba-2 (PRoject for OnBoard Autonomy).”

You can also see the slowed down YouTube version (also awesome).

Photo by Mai Blahg via tumblr.com under “biology” tag.

“The use of chopsticks requires a great deal of dexterity, making their use impossible by those without training, and often making their use undesirable by those who do not use them regularly, but who do not wish to risk the embarrassment of dropping or otherwise mishandling the food they are eating. … Accordingly, those wishing to avoid embarrassment while eating often must break with Oriental custom by opting for the less-embarrassing and less enjoyable alternative of using Western-style utensils when eating Oriental cuisine.” (Gerald L. Printz, 1987)

Via Futility Closet.

By DAVID NG

“You see something interesting…”

This little phrase is often the start of the scientific process. In that it all begins when someone, possibly you, has noticed something intriguing. This doesn’t mean that it has to be interesting to everyone – just as long as it’s interesting to someone. In fact, sometimes, the science will stop right there. In other words, the act of just “observing” might be good enough – think about how everyone would feel if you were the first to discover a certain kind of creature.

Still, most conventional views of science would assume that you’ve seen something curious enough to merit the question “why?” And it is in that inspired act of asking a question, where arguably the most important part of the scientific method takes form.

We are, of course, referring to the notion of the hypothesis: which according to the Oxford Dictionary is defined as:

“A supposition or proposed explanation made on the basis of limited evidence as a starting point for further investigation”

For us, in less eloquent terms, we say that this is the part where you try very hard to “think of a reason why.” Furthermore, when you do this, you inadvertently set the scene for the next stage of the method by defining how a person might “figure out ways to check your reason why.” To a scientist, this last phrase is a colloquial way of talking about experiments.

For fun, let’s explore these concepts by using an example. Here, we’ll focus on some interesting observations that were noted in China during the early 1980’s. Essentially, what folks observed was that there was a discernable decline in Chinese stork numbers [1]. As well, there was also a drop in fertility rates [2]. In other words, storks in China were disappearing and the Chinese appeared to be having less babies.

But why?

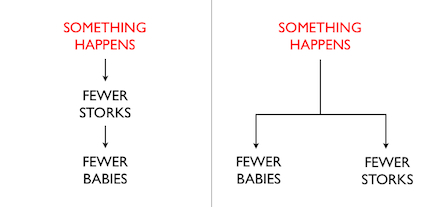

At one level, we might suppose that the two are not at all related. It could simply be a correlation and nothing more. But for the purposes of our discussion, let us suppose that we are trying to surmise whether the two are ultimately connected – whether there was truly a causative element involved.

Here, some of the hypotheses might assume that there is a continuum involved, in that one of the observations is actually directly responsible for and logically leads to the other observation. For instance, if we play into the stork/baby mythology, where storks do indeed deliver babies, perhaps we can say that the decline in stork numbers was in turn causing the baby effect. Others, however, might ponder whether there is a more central reason for the two trends. In this case, we might talk about a hypothesis that suggests one prominent thing at play that is simultaneously responsible for both outcomes.

Here, we can try to distinguish the two scenarios by looking at the evidence more closely. Does the stork decline happen before or after the baby decline? What exactly are the numbers associated with the declines? Important, because even with the drop taken into account, the actual numbers of storks might still be more than enough to cover the number of babies born. In any event, as you can see, a hypothesis can be quite nuanced and is really only a small step in a much longer path.

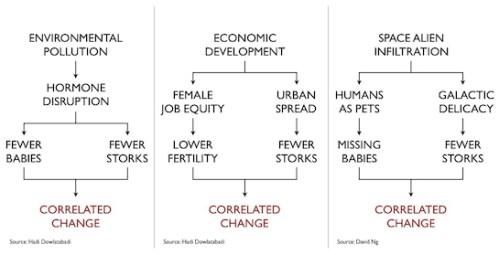

For amusement’s sake, let’s take this idea of nuance even further and look at the three potential hypotheses presented below [3]. Here, they all focus on a core reason (environment, economics, or aliens) that could explain our observations.

Looking at these flowcharts more carefully, you can see that when accessed logically, they all work. Even with the somewhat interesting inclusion of aliens, the fact remains that all three could be considered acceptable, worthy even. However, this is very different from a hypothesis being valid. Validity, which aims to make sure that what you say is indeed true, or at least true under every logical interpretation, is a much higher bar to meet. It is something that needs to be earned through the critical examination of evidence.

Now this is an especially important word, so we’ll once again invite the gravitas of the Oxford Dictionary to provide a definition:

“Ground for belief; testimony or facts tending to prove or disprove any conclusion.”

But such grounds can take several different forms, constituting strong or weak evidence. If we focus on the alien claim in particular, evidence might look a little like this:

1. We found an alien! And we have proof!

Here, we have important evidence from the point of view of addressing one critical question: are aliens real? It is crucial because it could be said that this detail is a major stumbling block in the alien hypothesis. However, proof of the existence of aliens isn’t in of itself strong evidence to support the hypothesis. This is because it doesn’t address any of the specific ideas and mechanisms put forth to explain our stork and baby narrative. Ideally, you would want to see data that demonstrated the involvement of our said alien with either storks or babies – actually, you would like to see both.

2. We found an alien eating a stork! We also found an alien with a baby on a leash! And we have proof!

This type of evidence is better, but it is still technically weak. This is because just having this data isn’t necessarily conclusive. What if the stork you see is, in actual fact, American? What if the pet baby is not Chinese? What if it is Chinese, but not in fact, from China? What if it is a result of alien cloning techniques? As you can see, the scientific mind will take what might otherwise appear convincing, and deconstruct it skeptically. A scientific mind will continually probe, and continually look for flaws in the evidence.

3. We found an alien eating a stork, and we have biochemical proof that the stork is from China! We found an alien with a pet baby, and we even saw the alien take the baby from a family in China! And we have proof!

Now, we’re getting closer, but now the issue is in the matter of whether this evidence represents an impactful occurrence. In other words, this particular data is really only good for showing the loss of one stork and of one baby. Obviously, this can hardly validate the observation that whole populations have dropped, which means that better evidence would also provide a better sense of the numbers involved. This particular stork and this particular baby could represent a simple coincident. Furthermore, what if this data was flawed for other reasons? Perhaps, if we had decided to observe the baby a little longer, we would have noticed that the baby was in fact being kept for food! This doesn’t change the fact that aliens may still be responsible for the drop in numbers, but it does nevertheless alter the sentiment of the current hypothesis significantly.

Of course, this type of review can go on and on. And the thing is: it does. What we have here is this continual cycle of coming up with hypotheses, coming up with ways to address the hypotheses, coming up with evidence, and then reevaluating everything over and over and over again.

Hopefully, you can see why this can very easily become an arduously slow process, although that’s not to say that it is always slow. More importantly, you should be able to appreciate how the process can lead to varying outcomes. It could lead to revisiting old ideas. It could naturally result in conflicting views. It could even cause your explanation (and also possibly the scientific discipline) to change directions dramatically. Imagine, if you will, that the real answer to our stork and baby scenario was a little bit about everything – a little mythology, a little environment, a little economics, and even a little bit about aliens. If this were the case, you could probably appreciate how difficult that complete story might be to tease out.

Here’s another thing to note: if you think about this process carefully, you will soon realize that the continual acquiring of scientific evidence never actually proves anything to be one hundred percent certain. It can only modify or support an existing hypothesis, although by supporting it relentlessly, a hypothesis can get stronger and stronger and perhaps one day rise to the rank of a scientific theory or scientific law. But even there, there is no certainty that there won’t be something that comes along to discredit that idea in a single stroke. This is Karl Popper’s take on the philosophy of science: that at the end of the day, you cannot prove something to be true: you can really only prove something to be false. This might take a moment to ponder, but if you do so with our alien example, you’ll note that this description does fit.

On the whole, our little alien discussion hopefully provides a window into how the scientific method works. But if we are honest with ourselves, we should also admit to glossing over something very important. Specifically, it’s in the parts where we have very nonchalantly uttered the phrase, “And we have proof!”

This bit, we will spend some more time on in the next section, as it considers how we distinguish strong evidence from weak evidence. Which is all the more daunting these days, since it’s quite likely you might not even understand the technical details of the evidence. Indeed, it might even be completely alien to you.

Notes:

1. Ma, Ming; Dai, Cai. “The fate of the White Stork (Ciconia ciconia asiatica) in Xinjiang, China”. Abstract Volume. 23rd International Ornithological Congress, Beijing, August 11–17, 2002. p. 352.

2. S Horiuchi. “Stagnation in the decline of the world population growth rate during the 1980s.” Science 7 August 1992: Vol. 257 no. 5071 pp. 761-765

3. Pollution and economic scenarios via personal communication with Hadi Dowlatabadi.

(3rd draft)

By Bob Dole, via “everywhere on the internet.”

“the creation of each design is a multistep and multimedia process. murayama begins with research and dissection of botanical specimens, photographing and sketching their parts. he then composes a 3D model in 3DS max, modifying individual elements in photoshop and matting the completed diagram in illustrator with captions and indication of scale.”

Via designboom.

But what exactly was responsible for this drastic change? Maybe there’s evidence out there for a punctuated equilibrium effect?

Illustrated by Charles Schulz, scanned from The Peanuts Collection (Little, Brown and Company, 2010), via Hey Oscar Wilde!

“By Heidi Sandhorst

Famous Physicists 2010 Trading Card Set for sale. 20 4″ x 6″ glossy cards with rounded corners featuring handmade artwork and information about each physicist on the back as well as an inspirational quote from each physicist. Each set comes in a black box with hand drawn label and gold rubber band to hold it shut. $20 plus s+h (if applicable).

Email me at heidisandhorst@gmail.com if you are interested in purchasing a set.”

Via Fresh Photons.

Whoa…

“Since the early 1990’s, I have been working with a type of illustration that shows portions of living cells magnified so that you can see individual molecules. I try to make these illustrations as accurate as possible, using information from atomic structure analysis, electron microscopy, and biochemical analysis to get the proper number of molecules, in the proper place, and with the proper size and shape.”

There’s lots more to see at http://mgl.scripps.edu/people/goodsell/illustration/cell.

Apparently the back leads with: “There may not be 6.02 x1023 avocados in here, but…”

A Trader Joe’s product, via gregamckinney.

Considering that it always seems like most superheroes got their powers via some sort of genetic mechanism, then maybe this graphic could be useful.

(Click on image for larger version)

By Pop Chart Lab.