January 9, 2012

Sciencegeek Fundamentals #4: In which a puzzle is not a puzzle, and instead illustrates scientific revolutions.

By DAVID NG

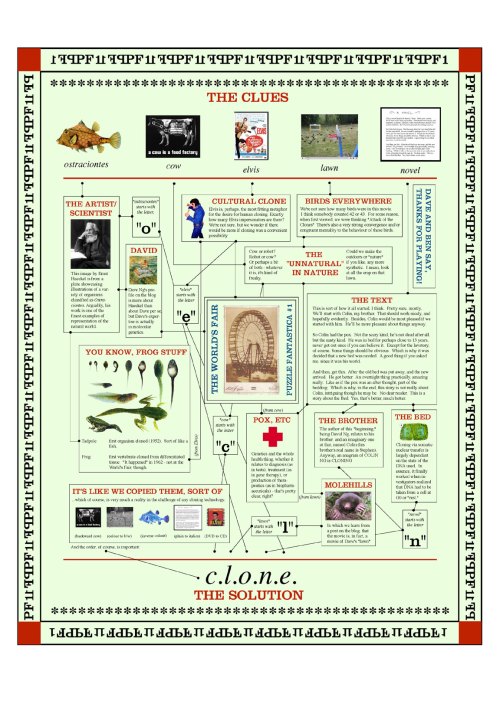

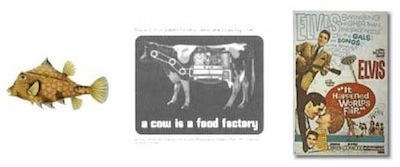

About five years ago, a colleague (Ben Cohen) and I decided to conduct a little online experiment. Essentially, we thought it would be fun to host a puzzle. This would involve the sequential release of some fairly bizarre pictures. The goal, of course, was to see if we could entice the denizens of the internet to play along – in other words, could they figure out what was the unifying connection between all of these strange things that they were seeing?

The formal start to this process involved the presentation of three images (shown above). This included: (1) a gorgeous picture of a fish, specifically one drawn by Ernst Haekel; (2) a picture of a robot masquerading as a cow masquerading as commentary on industry; and (3) the front cover of an Elvis Presley VHS tape (remember those?) called “It Happened at the World’s Fair.” We then gave this whole exercise the snazzy title, PUZZLE FANTASTICA, which was the sort of thing that precariously walked that strange line where it was simultaneously awesome and stupid. Next, we added the tag line, “Do not click unless you are of reasonable intelligence,” and then we basically just sat back and waited [1].

What happened next was pretty amazing. Immediately, we got a lot of feedback and a lot of attempts at solving the puzzle. And, I should add, a lot of it was very sophisticated and, well, remarkable. But despite this ingenuity from our readers, Puzzle Fantastica did not get solved.

And so, we released another clue… and then another. The fourth clue was a short movie of someone’s lawn covered with a few of those plastic climbing things that one purchases for small children, as well as about 100 European Starlings mulling through that same patch of grass. The fifth was some text, about a hundred words, which read as if it was the start of a strange children’s novel.

For each of these new clues, we saw new wonderful attempts at solving the puzzle, which interestingly enough, were often modifications of previous attempts. We also saw a huge increase in the number of participants, significantly fueled by traffic from other websites [2]. By the end of the exercise, we had managed to court several hundred different answers for our puzzle. However, despite this outpouring, none of these fine attempts had found the “official” answer.

Still, we were so impressed with the effort and the diversity of what we saw, that we made a fancy graphic of the totality of solutions presented to us.

Click on image to see larger version.

As well, at the time, Ben and I were a little worried. When all was said and done, we realized that when we put up our “solution” (a play on the word CLONE), we would also need to recognize the fact that many of the readers’ answers were far more elegant.

Still, the whole process was sublimed. It was in many ways, a microcosm of the scientific method in action. What happened was that folks “saw something interesting” (our clues), and then they tried to fathom from these observations, a reasonable “reason why?” In other words, they were coming up with hypotheses: and their manner of testing them was waiting to see if the next clue would support or contest them. The participation was truly brilliant, and it was a testament to how creative a person’s mind can be, when driven to the prospect of trying to understand something mysterious. It was also turning into a great analogy that we could use for teaching purposes: “Look, it’s like the scientific method!” we both said.

Except that the analogy had one completely mind boggling, over-the-top, truly delicous kink, which actually made it all the more richer. You see (and here’s the thing): in truth, there was no solution.

That’s right. The whole puzzle was, in actual fact, a complete ruse. We were simply interested in seeing how a community can seemingly find wonderfully intelligent ways to connect odd disparate observations. And it worked like a charm. Too well, actually: we hadn’t expected such large numbers of participants which was a little stressful and also the reason why we decided to fabricate a answer that fitted but also one that hadn’t already been mentioned. It was as if we were forcing ourselves into a paradigm of sorts.

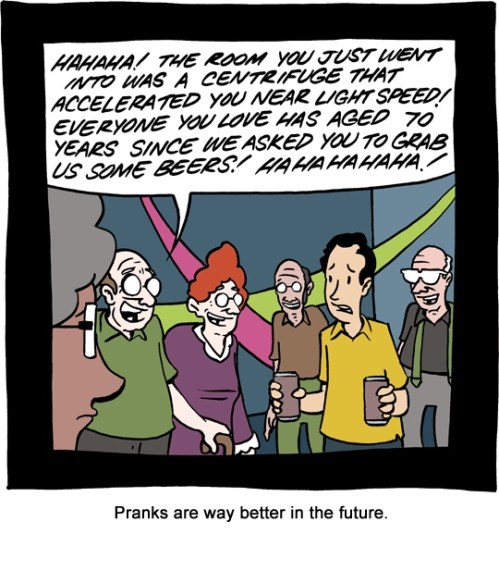

Which is fitting given what paradigms are in the world of scientific discourse. Here, Thomas Kuhn, the American Historian and Science Philosopher, famous for the publication of “The Structure of Scientific Revolutions,” says it best. He wrote that science “is a series of peaceful interludes punctuated by intellectually violent revolutions.” Furthermore, it is during those revolutions where, “one conceptual world view is replaced by another.”

What he was referring to was the idea that scientific discovery tends to work within paradigms. This is where there is an existing framework of knowledge that comfortably guides how observations are made, questions are asked, and how hypotheses are formed. However, history has also shown that on very rare occasions, these paradigms can change, and because they are so fundamental, such change can seriously rock the boat. We’re talking the Sun being at the center of the Solar System not the Earth; Einstein’s work on relativity over Newtonian physics; Darwin’s Natural Selection over all of that God stuff.

Our Puzzle Fantastica, admittedly by accident, actually illustrated how consequential a paradigm shift can be. In that our participants would have obviously acted in a completely different manner and would have provided completely different responses, had they known that there was never an answer in the first place. That particular change in our framework of knowledge for the puzzle was, suffice to say, revolutionary.

I bring this up, because it is yet another part of the scientific method. It is in many ways, the ultimate example of why Popper’s “You can’t ever prove the Truth” statement is so important. You just never know. Paradigm changes are actually implied with our scientific method flowchart, except without the intensity. In fact, it might be worth changing our flowchart to reflect this:

1. See something.

2. Think of a reason why.

3. Figure out a way to check your reason.

4. And? (very very very rare chance of a WTF in font 100 times larger!)*

5. Now, everyone gets to dump on you. (people actually freaking out!)*

6. Repeat, until a consensus is formed.

(* these grey bits refer to this paradigm business).

So there you have it: The scientific method in all of its glory. Although, hopefully, after reading through this material, you realize that this flowchart is still a gross simplification. Indeed, there are many who would prefer we not even call it the Scientific Method anymore. Instead, we should refer to it as the Scientific Process [3], as a way to highlight its fluidity and nuances, and that the flowchart should probably look a lot more busy and complicated with many criss crossing lines.

I personally like all of these , with maybe a secret desire to introducing a new term, Modern Baconian Method [4] – but that is just me. What might be most important from of all of this, is to just “get it.” It is just for everyone to have a certain degree of familiarity on how science can provide us with knowledge, and how that knowledge came to be.

Why? Because when you do, you’ll finally understand why the usual way we get our scientific information – that is, television, newspapers, the web and the like – is often completely fucked up.

NOTES

[1] Puzzle Fantastica #1: “Fish-Cow-Elvis” [do not click unless you are of reasonable intelligence]. Scienceblogs.com. (Assessed January 7th, 2012)

[2] Introducing Puzzle Fantastica. Boingboing.net (Assessed January 7th, 2012)

[3] Like these folks at Understanding Science.

[4] The Baconian Method, referred to earlier in part 1, is described here.

(3rd draft)

January 8, 2012

Ben Folds, Nick Hornby, & Pomplamoose: “Things You Think.” #song4mixtape

I had no idea that Dickens created about 13,000 characters in his life time. That’s impressive.

January 8, 2012

Sciencegeek Fundamentals #3: In Which We Discuss Expert Peer Review with a Bit About a Panda Named Steve.

By DAVID NG

On a cold and miserable evening sometime during the fall of 2006, I found myself sneaking into a 4 star hotel and gate crashing an international science philosophy conference. Yes… I am that wild.

O.K. admittedly, this might not sound like the most thrilling of endeavours, and certainly not something that would beckon a Hollywood screen writer, but it was nevertheless quite exciting to me. Not the least of which was because this act of rebellion led to meeting a minor celebrity. This is someone, who if you took the time to google, you would discover in various photo-ops posing with folks as varied as Steven Pinker, President Jimmy Carter, and even Martha Stewart. As well, the word “posing” doesn’t actually do these photos justice: rather, these well known individuals are literally holding him up.

Specifically, the celebrity I’m referring to goes by the name of Prof. Steve Steve, and the reason why he is always held is because he is, in actual fact, a small stuffed toy panda. True, he not necessarily a well known celebrity, but, he is definitely an inspiration in certain scientific communities for reasons related to an interesting decade long battle of words.

Specifically, these words:

“We are skeptical of claims for the ability of random mutation and natural selection to account for the complexity of life. Careful examination of the evidence for Darwinian theory should be encouraged.”

The above is a statement crafted by the Discovery Institute, a Seattle based think tank that primarily acts as a front to push the concept of “Intelligent Design” into public school science curricula. This is essentially the idea that elements of life were consciously “designed and/or created” by something with intelligence (for instance, a God or a tinkering alien, etc). It is more or less a supposed counterpoint to the science of evolution.

Since the statement’s release in 2001, the institute has also maintained a list of signatories, who are collectively referred to as A Scientific Dissent From Darwinism[1]. In other words, this is a list of folks with advanced degrees who insist that evolution is a scientifically weak concept. As of December 2011, 842 signatures had been collected, and the Discovery Institute has often claimed that this exercise is evidence that evolution is, indeed, highly debatable as science; and that other views, specifically views that ultimately include intelligent design (and ergo creationism) should be entertained and validated within science education.

This, of course, is rather silly – if not altogether disturbing to those who are scientifically inclined. And so in response, the National Centre for Science Education (NCSE) decided to launch its own statement to counter this awkward pseudoscience babble. Released in 2003, this one read:

“Evolution is a vital, well-supported, unifying principle of the biological sciences, and the scientific evidence is overwhelmingly in favor of the idea that all living things share a common ancestry. Although there are legitimate debates about the patterns and processes of evolution, there is no serious scientific doubt that evolution occurred or that natural selection is a major mechanism in its occurrence. It is scientifically inappropriate and pedagogically irresponsible for creationist pseudoscience, including but not limited to “intelligent design,” to be introduced into the science curricula of our nation’s public schools.”

And like the other statement, signatures were courted, where as of April 25th, 2012, the total number had reached 1208 individuals [2]. Apart from the empirically obvious fact that the Scientific Dissent from Darwinism has fewer signatures, it is also worth pointing out two other significant differences between the two opposing lists.

First, many have questioned the credibility of the Discovery Institute signatures. For instance, some argue that over the years, the signatures have often been inconsistently attributed (many titles are vague, university affiliations may be absent, current involvement in scientific activity suspect), and often signatories were not necessarily aware of the agenda behind the vague statement [3]. In addition, one also notices that only a small proportion of them actually have relevant biology backgrounds. In fact, in an analysis done in 2008, this was calculated to be just shy of 18%. In contrast, the same analysis determined that the robustly labeled NCSE list scored a much higher 27% [4].

Still, it is the second difference that is most noteworthy (in fact, it’s also brilliant). This is where every signatory in the NCSE list is named Steve… Or Stephen, or Stephanie, or Stefan, or some other first name that takes it root from the name “Steven.” Yes, even Stephen Hawking is on the list. Put another way, the list would obviously be much much larger without this restriction [5].

This is why the NCSE list is also known as Project Steve (an affectionate nod to noted evolutionary biologist and author, Steven Jay Gould), and this was also why it was very exciting to meet with Prof. Steve Steve. You see – he is the project’s official mascot, and he is a great reminder of why it is important to invalidate those who would be inclined to create controversy around the science of evolution, be it for political or religion reasons.

He is also a lovely reminder of the importance of another aspect of the scientific method. Specifically, this concerns the part where everyone gets to dump on you, or perhaps more accurately, the part where everyone – who’s an expert – gets to dump on you. It refers to the idea of how “proof” is accessed and validated. In science terms, we call this part of the method, “expert peer review.”

This is important because it dictates that scientific knowledge gets to be critiqued in a very particular manner. It gets examined in such a way, where one is left with a scientific opinion that:

(1) is based on the examination of tangible evidence, which is not only made publicly available for all to see, but is also described in enough excruciating detail so that anyone has the option to try to reproduce it (hence the existence of peer reviewed journals);

(2) is formulated by those who actually know what the hell they are talking about;

(3) is backed by the most numbers of people who actually know what the hell they are talking about; and

(4) did I mention the bit about people actually knowing what the hell they are talking about?

In other words, this idea of expert peer review is really really a good way of critiquing evidence and thereby evaluating the claims and the hypotheses they contend to support. Moreover, it is especially important because it provides a mechanism for general society to check things out – since not everyone in society has the necessary background to evaluate scientific claims and evidence. For instance, a non-geneticist may be hard pressed to fully assess DNA sequencing data; a non-computer scientist may be hard pressed to appraise the relevance of a climate model – but that’s o.k. since this is what expert peer review is set out to do. It sets out to gather the required community of scientists to check things out for you.

Such a review process is all the more pertinent because the reality is that it’s not that difficult for anyone to be convincing and still disingenuously utter the phrase, “and we have proof!” A Scientific Dissent From Darwinism is a good example of this. Which is why the rational protect themselves from such scams by relying on these communities of experts, who in turn are vested in the scientific method, and who strive to objectively and publicly analyze such sentiments for validity.

Which is to say, that clearly, the list of Steves win hands down.

Me (and Janet, John, John, and Ben) with Prof. Steve Steve at an international science philosophy conference.

– – –

NOTES:

[1] A Scientific Dissent from Darwinism. (Assessed January 7, 2012)

[2] Project Steve Website. (Assessed January 7, 2012)

[3] Doubting Darwinisms Through Creative License. (Assessed January 7, 2012)

[4] Project Steve: 889 Steves Fight Back Against Anti-Evolution Propoganda. Science Creative Quarterly. (Assessed January 7, 2012)

[5] For instance, on quick examination of the December 2011 edition, there are 10 individuals on the Dissent list who names would fit under the Project Steve criteria (all Stevens or Stephens). Given that this represents 1.19% of all the names on that list, we could then, by analogy, project that the NCSE could have easily produced a list of close to 100,000 names, had they not included the name restriction.

(3rd draft)

January 8, 2012

There are 40 animals in this box. Can you find the giraffe?

Brilliant image by Andrew Shek!

January 6, 2012

Dear Scientists of the world: don’t do this – Playing Devil’s Advocate to Win.

Instead, speak up. Seriously, we all know that most of the noisy ones out there are very disappointing (scientifically).

Via xkcd.

January 5, 2012

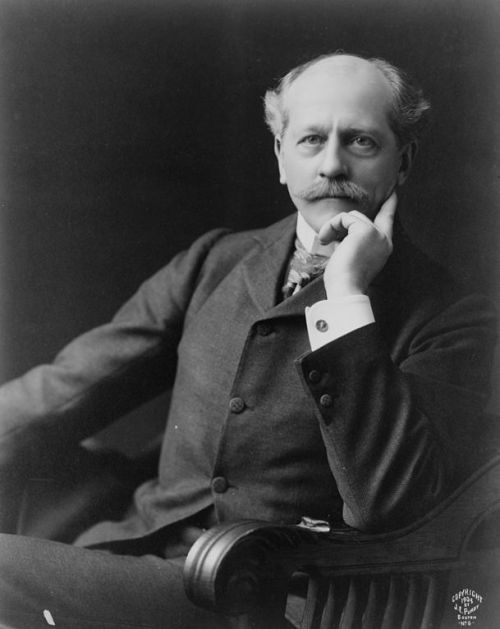

This dude strongly pushed the existence of intelligent Martian Canals. His initials also influenced the naming of Pluto.

Science history rocks! This is a picture of Percival Lowell. More at his wiki entry.

January 5, 2012

On the subject of MacDonald’s. Some obvious (and useless?) science.

REFERENCE:

Potential Effects of the Next 100 Billion Hamburgers Sold by McDonald’s. (2005) American Journal of Preventive Medicine 28(4) :379-381

ABSTRACT:

Background: McDonald’s has sold more than 100 billion beef-based hamburgers worldwide with a potentially considerable health impact. This paper explores whether there would be any advantages if the next 100 billion burgers were instead plant-based burgers.

Methods: Nutrient composition of the beef hamburger patty and the McVeggie burger patty were obtained from the McDonald’s website; sales data were obtained from the McDonald’s customer service.

Results: Consuming 100 billion McDonald’s beef burgers versus the same company’s McVeggie burgers would provide, approximately, on average, an additional 550 million pounds of saturated fat and 1.2 billion total pounds of fat, as well as 1 billion fewer pounds of fiber, 660 million fewer pounds of protein, and no difference in calories.

Conclusions: These data suggest that the McDonald’s new McVeggie burger represents a less harmful fast-food choice than the beef burger.